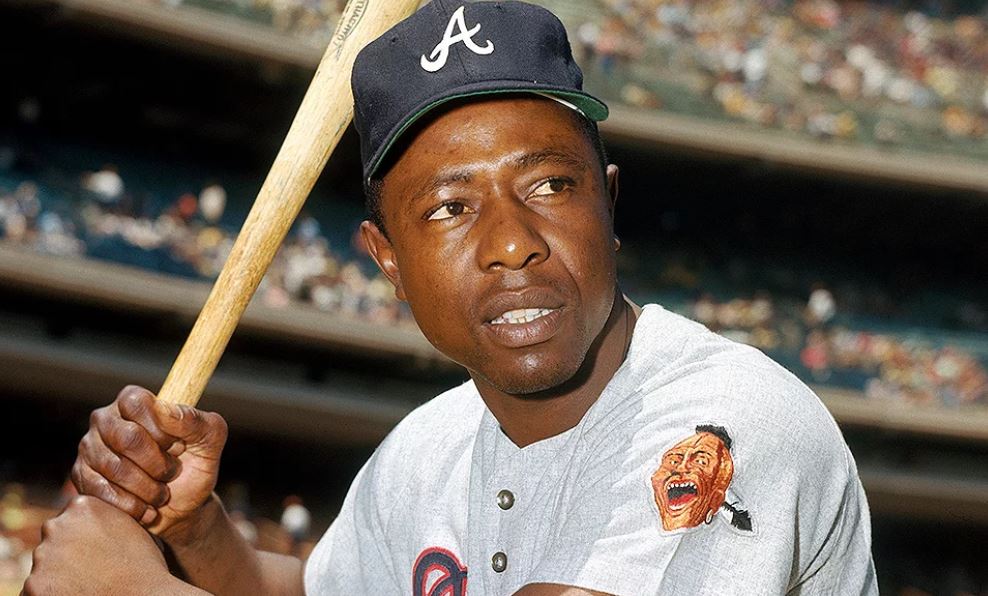

Hank Aaron, home-run-hitting baseball great, dead at 86

Hank Aaron, whose prodigious swing took him from a poverty-stricken section of Mobile, Alabama, to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, has died. He was 86.

Aron played 21 of his 23 seasons for the Milwaukee and Atlanta Braves, and Braves Chairman Terry McGuirk said he was heartbroken by the death of baseball’s one-time home run king.

“We are absolutely devastated by the passing of our beloved Hank. He was a beacon for our organization first as a player, then with player development, and always with our community efforts,” McGuirk said Friday in a statement.

“His incredible talent and resolve helped him achieve the highest accomplishments, yet he never lost his humble nature. Henry Louis Aaron wasn’t just our icon, but one across Major League Baseball and around the world.”

Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms called Aaron’s passing “a considerable loss for the entire city.”

“While the world knew him as ‘Hammering Hank Aaron’ because of his incredible, record-setting baseball career, he was a cornerstone of our village, graciously and freely joining Mrs. Aaron in giving their presence and resources toward making our city a better place,” she said in a statement.

Aaron had been seen in public as recently as Jan. 5 when he came to Morehouse School of Medicine to get his Covid-19 vaccine. He and former U.N. Ambassador Andrew Young got their shots in front of cameras and urged all Americans to seek vaccination.

Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp praised Aaron for “his important work to advance civil rights and create a more equal, just society.”

And former President Jimmy Carter, a native of Plains, Georgia, on Friday called Aaron a “breaker of records and racial barriers.”

“Rosalynn and I are saddened by the passing of our dear friend Henry Aaron,” the nation’s 39th president said in statement. “One of the greatest baseball players of all time, he has been a personal hero to us.”

Aaron wrapped up his 23-year career in the majors in 1976 with a raft of records that still stand, including 2,297 runs batted in, 6,856 total bases and 25 All-Star game appearances.

But the former Milwaukee/Atlanta Braves great is best known for a record that no longer stands — hitting his way to the all-time home run record previously held by Babe Ruth and later eclipsed by Barry Bonds.

Aaron, who slugged 755 home runs, showed little bitterness that the power mark was surpassed in a modern era that has emphasized long balls and has been helped along by better training methods and even doping.

When Bonds hit his 756th home run in San Francisco in 2007, the Giants played a videotaped congratulatory message from Aaron.

“It’s kind of hard for me to digest and come to realize that Barry cheated in the home runs,” the soft-spoken Aaron told NBC’s “TODAY” show last year, though he still calls Bonds the home run king of baseball and doesn’t believe other great players of the steroid era should be banned from Cooperstown.

The Babe’s record of 714 career home runs once seemed insurmountable, but Aaron surpassed the ex-Yankee with his No. 715 in front of his home crowd in Atlanta on April 8, 1974. Not everyone, however, was cheering as hard as Braves fans.

Aaron said on “The Dan Patrick Show” that he was deluged with racist hate mail and death threats as a Black player threatening the mark of one of the most popular white players to ever play the game. He said he kept all of the letters to remind his grandchildren how pervasive racism is in the country.

“In all of the interviews that the police and the detectives and whoever was in charge did, (they said) all of these were probably just crank letters, but there may be one in there from someone that meant something,” Aaron said in the October 2016 interview.

Negro Leagues Baseball Museum President Bob Kendrick on Friday reminded fans that Aaron broke with the Milwaukee Braves in 1954, just seven years after Jackie Robinson shattered the color line with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

So Aaron faced the same brutal racism other Black players of the era experienced, especially as the slugger approached Ruth’s home run record.

“This Black man in the deep South was about to break a record that no one really thought could ever be broken and that was not wearing well on a lot of (white) people,” Kendrick told the MLB Network, shortly after getting word of Aaron’s passing. “And yet he was able to withstand, endure and still perform at an exceptional level.”

Kendrick added: “He’s as much of a civil rights icon as anyone.”

Born Henry Louis Aaron on Feb. 5, 1934, the future outfielder was the third of eight children of a tavern owner. Given his athletic prowess, sports seemed to be a ticket out of his poor Black neighborhood in Mobile, as he starred in baseball and football first for segregated Central High School and later for a private school called the Josephine Allen Institute.

But he would quit before he graduated, having inked a contract as an 18-year-old with the Negro Baseball League’s Indianapolis Clowns. He only played part of the 1952 season, but served enough time to lead his team to a championship.

After Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier in 1947, a player of Aaron’s caliber wasn’t going to escape notice for long. He signed a $10,000 contract with the Milwaukee Braves, with whom he made his big league debut two years later.

In 1955, Aaron hit .328 with 27 home runs and 106 RBIs in his first full season, and won his first batting title a year later.

His sole National League MVP award came in 1957 courtesy of a stat line that included a .322 batting average, 44 home runs and 132 RBIs. That magical season would end with the only World Series title of Aaron’s prestigious career — a seven-game upset of the seemingly indomitable New York Yankees.

But what made Aaron arguably the greatest player in baseball history was a combination of longevity and consistency. He is one of only two players (along with Alex Rodriguez) who hit 30 home runs in 15 seasons.

The outfielder played most of his career with the Braves — 12 seasons in Milwaukee and nine in Atlanta after the team moved — but was traded back to Milwaukee, to the expansion Brewers, in 1975. He spent his final two seasons as a designated hitter for the American League squad.

He retired at the end of the 1976 season with 755 home runs and a career average of .305.

Aaron was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982.

Aaron, however, didn’t stay away from the Braves after he hung up his bat, eventually moving into the team’s front office, where he served as executive vice president.

To the end of his life, he remained a champion of minority hiring and inclusion in the sport he loved. In October 2018, the league renamed the Elite Development Invitational, the largest developmental program for minority players, in honor of Aaron.

Appropriately enough, MLB also awards the Hank Aaron Award to the best hitter in each league as voted on by the fans and the media.

Aaron is survived by his wife Billye and their children Gaile, Hank, Jr., Lary, Dorinda and Ceci, the Braves said.